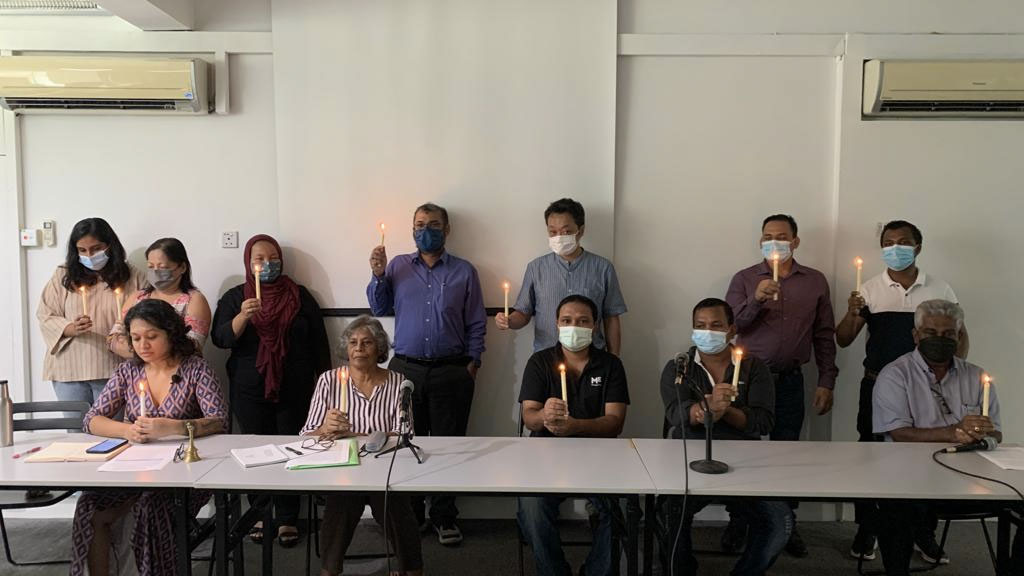

The Labour Law Reform Coalition (LLRC) holds its candle lighting activity to commemorate fallen workers on International Workers’ Memorial Day, April 28 (Photo courtesy of North-South Initiative)

PETALING JAYA, MALAYSIA – “Workers come to work to live, not to die,” said Irene Xavier, co-chair of the Labour Law Reform Coalition last April 28 during the organisation’s International Workers’ Memorial Day (IWMD) press conference.

Although Labour Day on May 1st is the most widely-known observance of workers’ rights and struggles, IWMD remains a solemn reminder of the millions of labourers injured and killed due to hazardous occupational conditions.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that migrant workers make up about20% of Malaysia’s workforce. Despite being abundant in resources and employment opportunities for migrants, the country faces an increase in human rights abuses owing to exploitative labour conditions, with the COVID-19 pandemic worsening the workers’ plight.

At the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, migrant workers in agricultural areas were among the first to lose their employment and immigration status due to lockdowns and delays in the renewal or creation of their contracts. Such delays have led to the detention of over 2,000 undocumented farmworkers across the country’s palm oil sector.

Aside from the loss of immigration status, migrant farmworkers, along with the rest of Malaysia’s foreign workforce, have seen a rise in deteriorating mental health due to the pandemic: prolonged isolation, coupled with delayed wages and a lack of health services and accommodation has severely impacted migrant workers’ already weakened physical, emotional, and psychosocial health.

Occupational Safety amid COVID-19

With the theme of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) for IWMD 2022, the press conference focused on the discussion of occupational conditions in Malaysia. According to Xavier, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the lack of OSH standards for migrant workers.

Migrant workers in Malaysia, said Xavier, were confronted with a lack of masks, checkups, and workplace access to hand sanitisers and personal protective equipment (PPE). Based on LLRC’s preliminary report presented by Tashny Sukumaran of the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia, the lack of COVID preventive measures in Malaysia even led to the deaths of workers.

Sukumaran recalled how a worker who complained of COVID-related symptoms to their employer was merely given a pain-reliever pill instead of access to medical care, and died of COVID shortly after. Such cases are not unheard of in Malaysia, where migrant workers are susceptible to COVID due to their cramped living spaces and lack of social distancing on top of the denial of healthcare access.

Sudden deaths, invisible injuries

The press conference highlighted the alarming rates of unspecified deaths and injuries among migrant workers. According to Sukumaran, the details of at least 64% of migrant deaths are unknown and are merely referred to as sudden deaths.

One Nepali migrant worker whose identity was withheld due to the risk of deportation shared that factory workers often suffer from high blood pressure and diabetes, and routinely work 12-20 hour shifts. The same worker responded that he noticed several co-workers dying in their sleep with the deaths reported as unspecified. The exploitative working conditions faced by factory workers are given little notice despite the highly possible link between the two.

Unspecified injuries, too, reportedly plague the workplace. According to Xavier, visible injuries (such as cuts, bruises, or amputations) are easier to address than those considered as invisible like the rise of cancer cases among women workers in electronic factories across the country. Due to the delayed onset of cancer and the lack of research on the possibly-carcinogenic chemicals used in the workplace, the correlation was supposedly difficult to prove despite the actual experience of workers.

Cutting Costs, Low Accountability

Already confronted with hazardous working conditions, migrants also face financial strain and a lack of accountability from their employers. Aside from being denied of their wages for years, Malaysian migrant workers lack channels for redress when reporting mistreatment in the workplace.

A Nepalese migrant shared that several workers felt they were not eligible for social protection under the Malaysian Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) due to being unregistered by their employers, leading to lower cases of reported workplace hazards and maltreatment. In a similar vein, issues such as sexual harassment among female workers have gone mainly unreported due to the lack of social protection.

The discussion on social protection was extended to the lack of accountability from employers. Based on narratives from the press conference, employers with a history of OSH violations rarely face legal consequences.

In Memory of the Workers

The words of N. Gopal Kishnam, LLRC chairperson and speaker at the event rang true for workers in Malaysia and across the world: “Jobs shouldn’t kill.”

International Workers’ Memorial Day and Labour Day continue to be observed annually in the struggle for just and equitable working conditions. Amid inter-connected adversities brought about by economic crises, pandemics, armed conflict, and climate change, the growing global labour movement, including the millions of migrant workers, remains a testament to the strength of collective struggle.

As the venue’s lights were turned off to make way for a candle lighting activity, the organizers closed the event with a moment of silence, followed by a resolve to commemorate fallen workers and sustain the collective fight against exploitative working conditions. ###